“Excellence in CX” Awards 2023

We have the privilege of partnering with some of the most amazing organisations in the world who are working hard to ensure that their customers’ (and employees’) voice drives strategy across all areas of their business.

We are excited to share some of the great CX work that we see daily while working with them.

At Deep-Insight we are not interested in vanity projects. We are proud to work with customers who align with our mission to ‘Inspire Transformation’ based on open and honest feedback from customers. That is what our Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ) framework and methodology is designed for and is what we are focusing on for these awards.

4 Award Categories in 2023

Last year we had four categories and made four awards.

This year we also have four categories but the awards are a little different. We are keeping the ‘Best CRQ Newcomer’ award but adding some different categories including one that will reward one of our clients for its focus on Employee Relationship Quality (ERQ) which is arguably as important as CRQ.

Best CRQ Newcomer

We award this prize to a company that has never deployed Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ) before but embraces the CRQ approach for the first time with gusto, takes the client feedback seriously, and truly commits to improvement.

Best CRQ Engagement

Engagement is all about convincing customers to give their feedback and working with you to help you make significant improvements. The winner is the company that does the best job at eliciting feedback from customers.

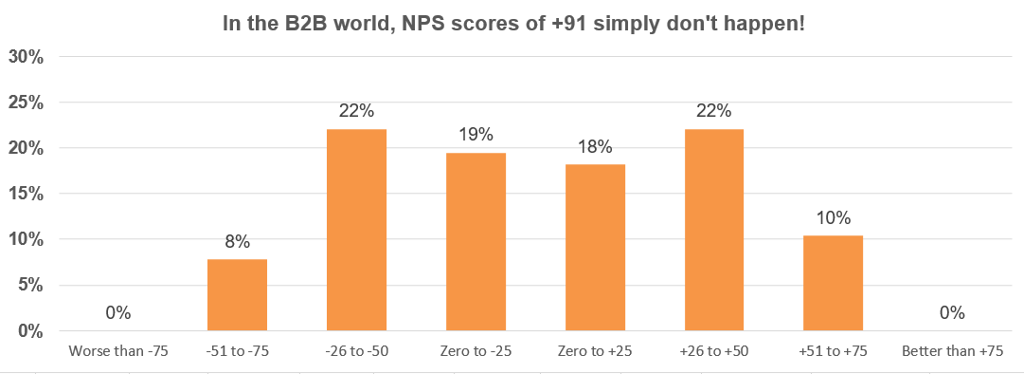

Best CRQ Score

We know that Customer Experience is not all about the score, but we feel it is still worth recognising the company that recorded the best Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ) score in 2023. Remember that customer centricity isn’t easy!

Best Focus on ERQ

Doing the right thing for customers means doing the right thing for your employees. We award this prize to the company that shows the greatest interest in Employee Relationship Quality (ERQ), the sister methodology to CRQ.

Next week we will announce the winners.

Let the Games Begin!

A Reminder of the 2022 Winners

Vreugdenhil Dairy Foods was awarded ‘Best Newcomer to CRQ’. This is a truly deserved award as Vreugdenhil embraced the CRQ process like they had been at this for years, and kept their momentum up all through the live survey and afterwards.

Six Degrees won the ‘Best Leadership Response to CRQ’ award. Everything in Customer Experience starts with leadership commitment and drive, and Six Degrees have this in spades.

invenioLSI was awarded ‘Best CRQ focus amid change’. This is a truly deserved award for an organisation that has seen exceptional growth and transformation over the previous 24 months.

BT Ireland won ‘Trailblazer in CRQ’ for its courage in leading the way in customer experience. They disrupted an already successful Customer Relationship Quality programme in order to re-focus the entire business on the basics – the value of growing customer relationships.