The Lionesses have a Net Promoter Score of -82

Back to one of my pet topics: What is a ‘Good’ Net Promoter Score?

More specifically, what’s a good Net Promoter Score score for a football team? OK, I know NPS wasn’t designed as a footballing metric but bear with me as I try to illustrate a point about how Net Promoter Score works and how NPS scores are significantly lower than most people think.

Let’s have a look at two fabulous teams that battled it out in the 2023 Women’s World Cup Final in Sydney last Sunday: England and Spain.

How did the Lionesses score in NPS terms?

I first looked at NPS for football teams in 2020. That year Liverpool won the Premiership for the first and only time and did so with a Net Promoter Score of -45, based on the player ratings of the Liverpool team.

Based on their performance in the Women’s World Cup Final last weekend, England’s Lionesses have a Net Promoter Score of -82. If you include the three English substitutes, their NPS drops to -86.

That’s not my view. It’s based on the player ratings for the starting 11, as compiled by The Guardian’s Louise Taylor in the aftermath of their 1-0 defeat to Spain. And Louise Taylor is not being particularly harsh. Most English – or European – sports commentators adopt a similar approach to scoring.

It’s not that England were poor last Sunday. They played well in the Final and had a great tournament. They were unfortunate to be matched against a Spanish team that was simply brilliant. Spain controlled the game superbly from beginning to end. Their passing was sublime. Olga Carmona’s goal was inch perfect. It had to be to beat Mary Earps.

By the way, Mary Queen of Stops was only rated 8, despite a penalty save late in the game. That’s a ‘Passive’ in Net Promoter terminology.

A quick recap on the scoring system: 9s and 10s are Promoters. 7s and 8s are Passives. 6 and below are Detractors. The Net Promoter Score itself is the percentage of of Promoters MINUS the percentage of Detractors.

Have a look at Louise Taylor’s player scores for the starting 11 below. 0% Promoters; 18% Passives (that’s two players: Earps and Hemp); 82% Detractors. That’s how the -82% NPS result is calculated. 0 – 82 = -82.

So did the Lionesses deserve a NPS of -82? Of course not. But at least the victorious Spanish team scored well in the NPS stakes. Or did they?

ENGLAND PLAYER RATINGS

Mary Earps. Mary Queen of Stops made vital saves from Paralluelo at the near post and Caldentey before denying Hermoso from the penalty spot. Had no hope of saving Carmona’s goal. Sometimes furious with her defence. 8

Jess Carter. Her great late block from Hermoso epitomised a fine tournament contribution. Coped well with second-half switch from right-sided central defender in a back three to left back and generally held her own. 6

Millie Bright. England’s captain advanced from central defence to join the attack in the closing stages. Sometimes struggled to cope with Paralluelo’s pace and movement but her decent positional play almost certainly kept the score down. 6

Alex Greenwood. Required a Terry Butcher-style head bandage after being caught by Paralleulo’s knee late in the second half. Showed flashes of her classy distribution but, for once, it was not enough from the elegant defender. 6

Lucy Bronze. Targeted by Spain and at fault in the preamble to Carmona’s opener, losing concentration and possession after taking one touch too many. A big mistake and too reckless at times. 4

Georgia Stanway. Did not see as much of the ball as she would have wanted and proved wasteful in possession but worked hard to help protect her defence. 5

Keira Walsh. Not at her best in the final – or the tournament – and still looks slightly uncomfortable in a midfield five. Struggled to retain possession. Conceded a handball penalty awarded after a lengthy VAR review. 4

Rachel Daly. Like Bronze, targeted by Spain and often pinned back by advances from Batlle, Bonmati and Redondo. Replaced by Chloe Kelly as England switched to a back four at half-time. 5

Ella Toone. Preferred to Lauren James in the starting XI but her poor positioning and slow reaction exacerbated Bronze’s error before Carmona’s opener. Replaced by Beth England in the 86th minute. 4

Alessia Russo. Worked as hard as ever but largely isolated as Spain dominated possession and was replaced by Lauren James at half-time. 5

Lauren Hemp. Reborn in a central attacking role, Hemp scared Spain, hitting the bar with an accomplished first-half shot. Should have scored after connection with a Kelly cross. Harshly booked. 7

Substitutes

Lauren James. Back for the second half after a two-match suspension but initially struggled to get on the ball before later growing into the game. 6

Chloe Kelly. Ran at Spain with menace and crossed brilliantly for Hemp but failed to supply sufficient killer final balls. 6

Bethany England. 6

The Spanish performance: NPS = +9 (or maybe -7)

As I said, the Spanish team performance in last Sunday’s Final was magnificent. So what was their Net Promoter Score? Surely it was +50 or higher?

Actually, Spain’s NPS was a paltry +9. If you include the three Spanish subs, its NPS was -7. Yes, that’s right – a negative NPS for the 2023 World Cup Winners.

How can that be?

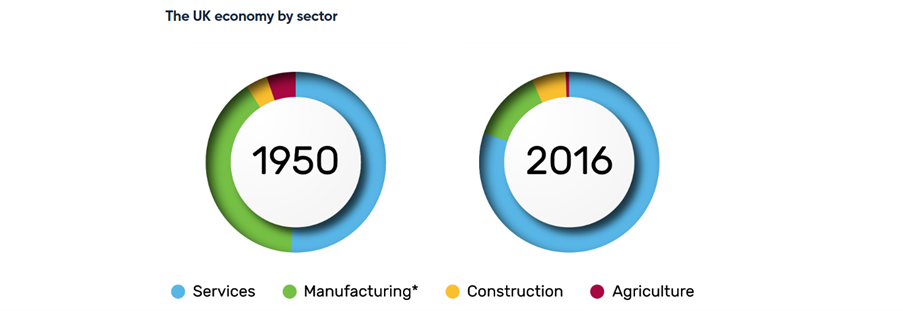

The answer is pretty simple. Net Promoter is an American scoring system that rates advocacy on a 0 to 10 scale and only recognises scores of 9 or 10 as excellent. Americans tend to score more positively than Europeans. Northern Europeans are particularly tough in the way they score. 9s and 10s are generally reserved for extra-special performances.

It’s a culture thing.

Look at the player scores below. Only 2 Promoters in the Spanish side: the goal scorer Olga Carmona and midfielder Aitana Bonmati. That’s 18% of the starting 11. Subtract 9% for the one Detractor (Jennifer Hermoso, and no, she didn’t have a bad game). NPS = 18 – 9 = +9.

If the three substitutes are included, that an additional 7 (Passive) and two 6s (Detractors). Now the NPS score becomes 14% (2 Promoters out of 14 players) minus 21% (3 Detractors out of 14). 14 – 21 = -7.

SPAIN: PLAYER RATINGS

Cata Coll. Spain’s inexperienced goalkeeper saved smartly from Lauren Hemp early on and Lauren James late on. Well protected by her defence and not really threatened by England but did not put a foot wrong in only her fourth senior appearance. 7

Ona Batlle. Stretched England when advancing from right back and combined well with Aitana Bonmatí. Gave Rachel Daly quite a workout and defended extremely well too. 8

irene Paredes. Sent a first-half chance flying wide and repeatedly second-guessed England’s attacking intentions superbly. 8

Laia Codina. Defended well before limping off injured to be replaced by Ivana Andrés in the 73rd minute but, unsportingly, got Lauren Hemp booked. 7

Olga Carmona. Her third goal for Spain was a piece of left-footed technical perfection directed low into the bottom corner. It deserved to win a World Cup. Defended well, too. 9

Aitana Bonmatí. Brilliant and utterly irrepressible. Showed off a wonderful change of pace as she regularly fazed England. Fractionally off-target with fine second-half shot. Too hot for the Lionesses to handle. 9

Teresa Abelleira. Helped Spain hog possession and ensured that England’s increasingly midfield were left chasing shadows. 7

Jennifer Hermoso. Had a second-half penalty save but that was about the only moment nerves got the better of the midfielder. 6

Alba Redondo. An important outlet for Spain down the right. Her low crosses created some good chances but faded slightly in the second half and was replaced by Oihane Hernández after 59 minutes. 7

Mariona Caldentey. Saw a shot brilliantly saved by Mary Earps after nutmegging Lucy Bronze early in the second half. Replaced by two time Ballon d’Or winner Alexia Putellas after 89 minutes. 8

Salma Paralluelo. The 19-year-old Barcelona winger has been a star of the tournament and her quick, clever feet stretched England. Should have scored. Reminded England she was once a star 400m runner. Hit a post. Booked and very lucky not to receive a second yellow late on. 7

Substitutes

Oihane Hernández. The right-back arrived on the wing to help maintain Spain’s lead. 7

Ivana Andrés. 6

Alexia Putellas. 6

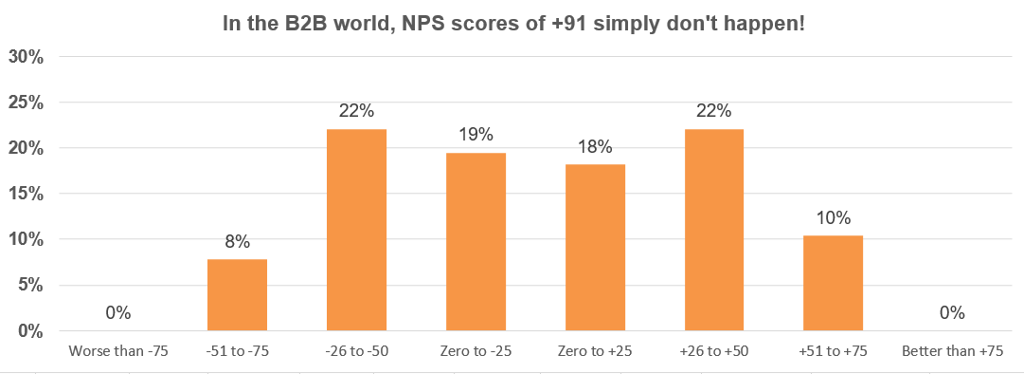

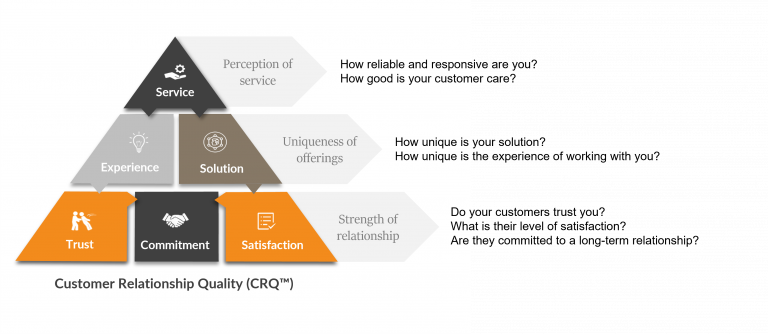

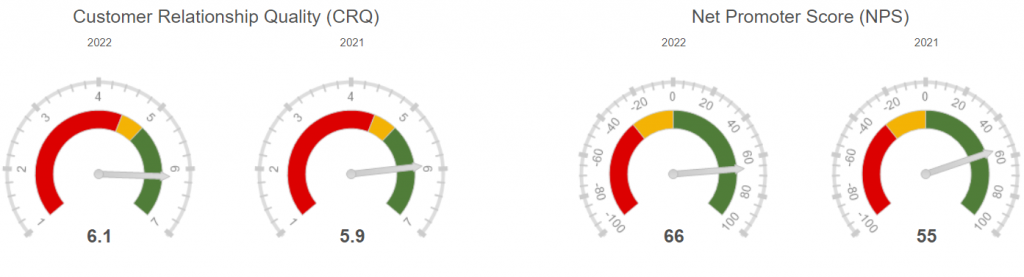

The average B2B Net Promoter Score in Europe is not much above zero

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote another blog called Things that never happened: a NPS of +91. Same topic; same message.

B2B companies may claim very high Net Promoter Scores but the reality is quite different. An average NPS result for a Northern European B2B company is only +3. Close to half of companies will have negative scores.

Rarely will European B2B companies score greater than +50. That’s a truly exceptional performance.

Don’t believe everything you read on the Internet!