This blog is a shortened version of The CX Factor which originally appeared in the October 2021 edition of Modern Lawyer. Modern Lawyer is published by Globe Law and Business.

Download the article, including the case studies with Baker McKenzie, DWF, Shoosmiths and Travers Smith by clicking on the image below.

SUMMARY

There’s a lot of talk at law firms about client relationships. For many clients these can still seem hollow words based on one-way relationships.

Robert Millard and John O’Connor explore how firms that are trying to embrace true client centricity are setting themselves apart.

The CX Factor

Much has been written over the years about how difficult it is for clients to differentiate between one law firm and the next. From a client perspective, law firms all look remarkably similar. Trust, reputation and brand generally play an unusually important role in buying professional services.

Appearing in directories such as Chambers & Partners, Legal 500 and International Financial Law Review are also important as are word-of-mouth recommendations. These are recognised to be among the most compelling means of winning new clients.

But what keeps clients loyal? What drives client relationship longevity? Except for the most complex or unique of matters, a range of firms exist from which clients can choose. Those firms are all staffed by highly competent, capable lawyers.

Making the Transition from Client Listening to Customer-Centricity

Within ranges, all charge roughly similar fees for similar matters. All are highly attentive to service quality. Most engage in at least some form of client listening. They claim to mould their services and service delivery channels around the needs of clients. But have they?

In our opinion, few have transitioned from client listening to becoming truly customer-centric.

This article is aimed at helping law firms to make that transition. The content is based on client- centricity work that John O’Connor has done with many large corporates and financial institutions, including DWF Group plc. It is also based on Robert Millard’s unparalleled understanding of modern law firms.

It was informed by interviews with Baker McKenzie LLP (Ana-Maria Norbury and Deanna Gilbert), DWF Group plc (Zelinda Bennett), Shoosmiths LLP (Peter Duff and Gaius Powell) and Travers Smith LLP (Julie Stott and Charlie Rogers) about their CX journeys. All of these were exceedingly generous with their time and insights. We thank them most sincerely.

Clients’ Demands are Shifting

Across many industry sectors and geographies, customers are shifting the ways in which they choose suppliers and service providers. Current research in the United States shows that the percentage of clients recommending law firms is at an all-time high of 69%. That’s up from 49% in 2020 and from 47% in 2019.

This increase is remarkable. But those results are not from superb skill in solving legal problems alone – the focus on service quality has given way to one of client experience (CX). For all but the most complex and difficult of services, service quality is no longer a source of sustained competitive advantage. It is a prerequisite to be even considered.

Clients now demand that their experience with the firm advising them be hassle free, transparent and even emotionally uplifting. They also expect law firms to look further than the legal advice. They expect them to help solve business problems.

Law firms are changing their business models in line with these shifting client requirements. But too slowly, in our view. The time has come to accelerate. Bluntly, modern law firms must move from client listening to more detailed conversations, and act decisively on what they discover.

No UK law firm has what a leading corporate or financial service client would acknowledge to be a world-class CX programme, or true customer-centricity. Pockets of excellence do exist though, and some of these can be seen in the case studies at the end of this article.

CX is Different to Service Quality

The concept of ‘quality’ emerged from the total quality management (TQM) movement of the 1950s. In the early days, the focus was on product quality. The emphasis moved in the 70s and 80s to service quality as economies in the western world became more services-based economies. ‘Client satisfaction’ became a prominent metric.

Client experience (CX) is different. It means that a firm’s core focus is on its entire relationship with its clients – not just on satisfaction. Contemporary research shows that CX is generated through a long process of interaction between a firm and its clients, across multiple channels and through generating both functional and emotional effects.

To achieve this requires ‘client-centricity’ which, in simple terms, means putting clients at the very heart of the firm. This transcends quality, to mean all the firm’s lawyers and business services professionals viewing every aspect of the firm from the client perspective. In this article, we use the terms ‘client centricity’ and ‘CX’ interchangeably.

For clients, quality assurance is difficult in legal and other professional services. Lawyers and other professionals frequently have more knowledge of the topic in hand than do their clients. This creates a ‘power asymmetry’. Work product is frequently co-created with clients, or at least based heavily on client inputs. Consistently poor performance leads inevitably to reputational damage, sanctions for professional negligence and, ultimately, failure.

The Intangibilty of CX in the Legal World

That much is clear. How, though, does a client assess whether services rendered in a specific matter were merely ‘good’, or ‘excellent’?

It turns out that it is far easier for clients to assess how they feel about the services and about their experience, than the objective quality of the service received. Clients must trust the professionals that they instruct to be technically competent and diligent. Such trust is not necessary to assess their reaction to their experience – their ‘gut-reaction’ – to dealing with the firm and the way in which the firm deals with them.

At an event held at White & Case’s offices in London some time ago, the former chairman of Allen & Overy (A&O), David Morley spoke of a very complex, challenging transaction where A&O was pitching for the legal advisory work against the usual range of premium London law firms. A&O won the engagement and, he said, he was later told by the client’s general counsel that the reason for that was that they felt that when, late at night in the midst of the deal when pressures were immense, they believed that A&O’s lawyers would be the easiest to deal with.

This is an excellent example of how intangible CX can be.

Professional Services are Different

Professional services have always been recognised as being distinct from products, and from other types of services. More than two decades ago, professional services were defined as:

- highly knowledge intensive, delivered by highly educated people, frequently linked to cutting-edge knowledge;

- involving a high degree of customisation;

- involving a high degree of discretionary effort and personal judgement on the part of the professional creating and delivering the service;

- requiring substantial interaction with the client; and

- being delivered within constraints of professional norms of conduct, including setting client needs above profit and respecting the limits of professional expertise.

For much of the past century, this has been an accurate description of the services delivered to clients by lawyers. Ask any lawyer if they are concerned about their clients, and the quality of services that they deliver to them, and the answer will almost always be: “of course I do!” And that response would be sincere and truthful – to the extent even that the question might be regarded as facile.

Commoditisation

Yet the statistics for clients defecting to rival firms in recent years have been alarming. Legal services are also changing. On the one hand, the complexity of legal issues increases continually and exponentially.

On the other, it is becoming difficult to justify including the more process-driven ‘commoditised’ services under the umbrella of professional services. This does not mean that law firms need to discard these services. They form an important part of the business of many law firms.

The term for services that are not ‘professional’ is not ‘unprofessional’. It’s ‘technical’. The fact is that clients view technical legal services through a different lens, and the profit drivers of these services are different to those of professional services. The firm’s business model needs to be more granular if the tensions between these client expectations and profit drivers are to be managed.

As the ‘4th Industrial Revolution’ unfolds, more of the services now delivered by people will be better delivered by technology. Some lawyers will focus on using ever-more complex technological tools to advise clients on meeting their own increasingly difficult, complex needs. The business of law is also being disrupted by emerging digital technologies and the geo-economic impacts that they spawn. Some firms will build highly profitable legal service platforms (LegalZoom being a good current example) to focus on more mainstream legal needs. Best CX practice will evolve differently for each.

These tensions can and must be managed. CX has proved a valuable tool for banks, retail organisations, airlines and others to improve levels of customer satisfaction. It is now gaining rapid traction with law firms and might even be a new frontier on which law firms are competing. Many firms, however, appear to be struggling to separate the concept from similar ones such as ‘service quality’ and ‘client relationships’ and ‘client listening’.

What to Measure?

Metrics are obviously crucial. One of the best-known CX metrics is Net Promoter Score (NPS), created by Fred Reichheld based on his work at the consulting company Bain & Co. In his book The Loyalty Effect, Reichheld stated that clients should be valued according to the net present value (NPV) of the future revenues to be earned from them. This has given rise to the notion of client lifetime value (CLV).

NPS is based on the proven premise that client relationship longevity can be predicted by a client’s response to a single question: “how likely would you be to recommend our firm to a friend or colleague?”

Reichheld’s research showed that surprisingly high NPS scores are required to indicate long-term client loyalty. The NPS of a firm overall is calculated by subtracting the percentage of clients who allocated a score of 6 or less (Detractors) from the percentage who allocated a score of 9 or 10 (Promoters).

NPS scores can theoretically range from –100 to +100. An average NPS for a European B2B company is around +10 while an average score for European professional services firms is around +30.

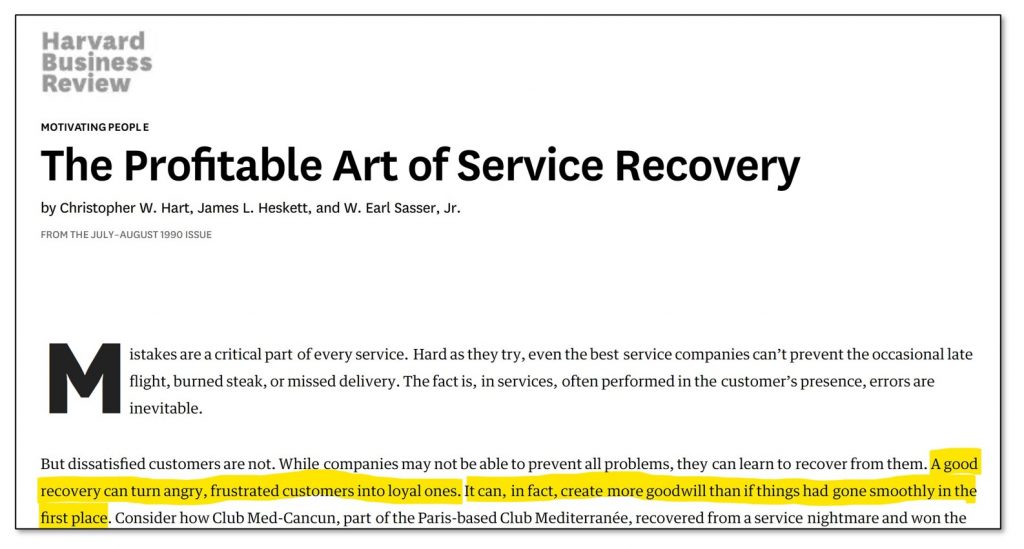

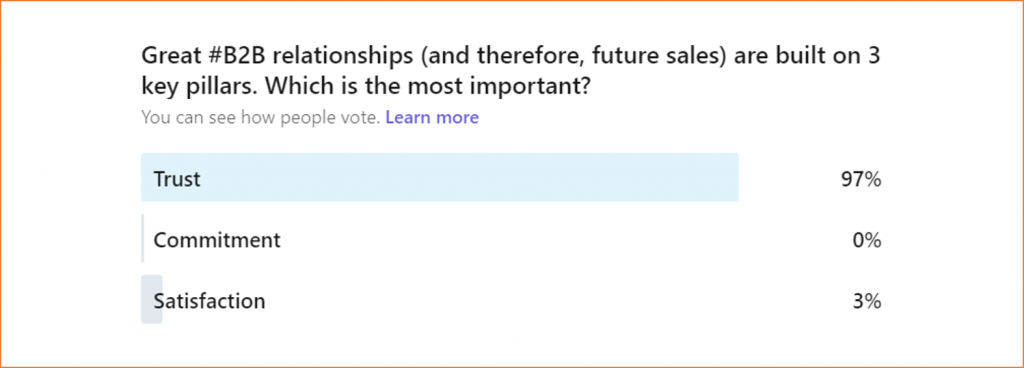

But is NPS the best metric for law firms? We mentioned earlier how A&O won an engagement based on the general counsel’s level of Trust in the firm’s ability to deliver when the going got tough. Few companies measure trust explicitly – yet it is the fundamental building block of any client relationship.

Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ)

An alternative to NPS is to view the client relationship more holistically. Client relationship quality can be visualised as a pyramid comprised of three different levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Customer Relationship Quality (CRQ) model

Three levels of Customer Relationship Quality

The first and most fundamental is the Relationship level. Do your clients trust you, are they committed to a long-term relationship with you, and are they satisfied with that relationship?

The second is the Uniqueness level. Do your clients view the experience of working with you, and the solutions you offer, as truly differentiated and unique?

At the top of the pyramid is the Service level. Are you seen as reliable, responsive and caring?

If law firms score well on all six elements of customer relationship quality (CRQ), their clients will act as ambassadors, generating a high NPS.

NPS and CRQ scores are highly correlated. Law firms should track their NPS but in order to understand what that is really telling you – and what you have to do to improve that score – law firms also need to measure and understand all six elements of the CRQ model.

Turning ‘Client Listening’ into an Effective CX Programme

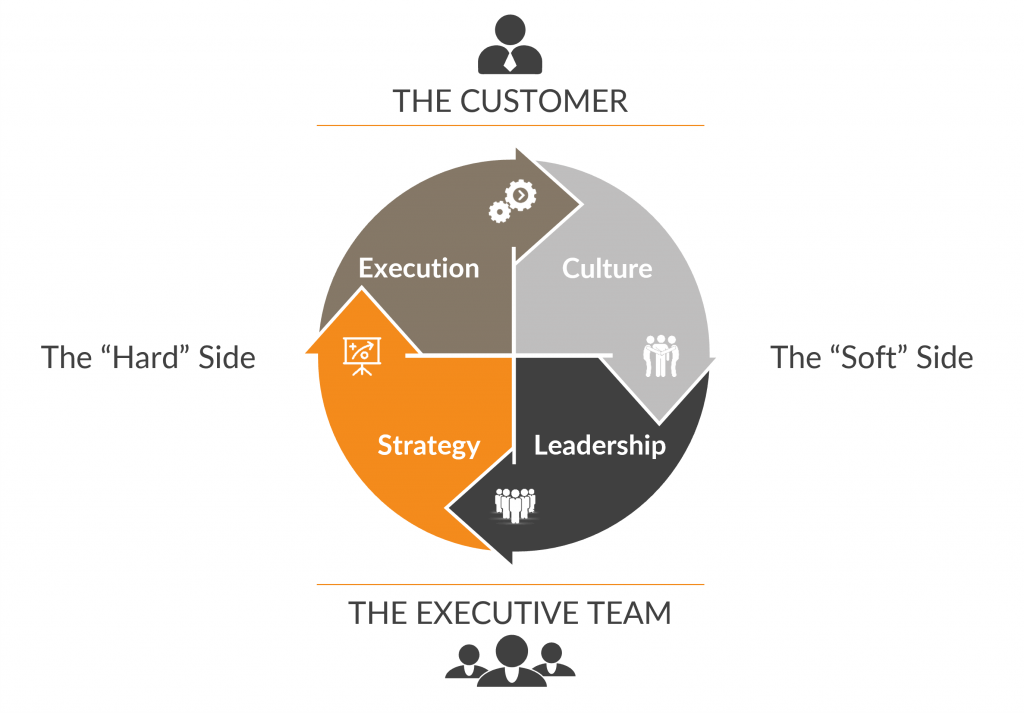

Client listening is obviously more than just the score and the verbatim feedback that is captured. A fully-fledged CX programme is also far more than a client listening survey. It includes what we refer to as ‘hard side’ and ‘soft side’ activities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Deep-Insight CX framework

The four quadrants are:

- LEADERSHIP. The most important quadrant. Good customer excellence (CX) programmes are always led from the top.

- STRATEGY. Good CX programmes link customer, product, operational and organisational strategy explicitly to customer needs.

- EXECUTION. Success requires properly resourced teams that are brilliant at executing the strategy.

- CULTURE. Finally, customer excellence must become integral to the DNA of the organisation: “it’s how we do things around here”.

The hard side activities of Strategy and Execution are important. These include setting up the CX programme, determining what to measure, executing the survey process, and using the client feedback to update company strategy. However, one of the key lessons from interviews with corporate leaders is that successful CX programmes require heavy investment in ‘soft side’ activities if they are to generate real long-lasting results. This means spending significant amounts of time with law partners and client teams planning for success.

All four quadrants are necessary for a successful CX programme. Many law firms start at the execution quadrant and are often disappointed when their client-listening programme produces no meaningful result or change. In our experience, the soft side is often overlooked and almost always under-resourced. Leadership is the most important quadrant while culture is the most challenging.

Step 1. Drive change from the leadership level

Client relationship longevity is a crucial building block of the firm’s client value proposition (CVP). It deserves the attention of the firm’s most senior leaders. Without active and highly visible senior leadership support, a firm is unlikely to achieve the CX results that they need to build sustained competitive advantage. It is crucial that the firm’s leaders themselves be truly client-centric. The must:

- Be genuinely passionate advocates for the firm’s clients and their interests;

- Take personal ownership of enhancing client- centricity in the firm;

- Have an intuitive understanding that client satisfaction drives financial success;

- Use client-centricity as a lever to effect organisational change; and

- Be relentless about execution.

This list might appear daunting, but it is crucial. Too often, a firm’s CX initiatives founder because the task is delegated to mid-level teams who have no more than lukewarm support from senior leadership. The result? They are unable to drive the degree of change that can really make a difference. The need for active and visible senior leadership support is evident in the comments of Peter Duff, chairperson of Shoosmiths, in Case Study 1.

Step 2. Link Strategy Explicitly to Actual Client Needs

Once the leadership for the CX programme has been secured, the law firm must use the voice of the customer to drive all aspects of the firm’s strategy. This can, and often will, involve major organisational and operational change. It will also require changes to the firm’s business model (CVPs, resources and profit model). O’Connor and Whitelaw devote an entire chapter of their book Customer at the Heart to the strategy of client-centricity.

In Case Study 2, Zelinda Bennett speaks of some of the major strategic changes that DWF Group have made in order to serve their global clients more effectively. Reorganising the business into global divisions and acquiring an alternative legal services provider (ALSP) were bold and decisive actions taken precisely because DWF wanted to become more client-centric.

Strategy must involve all aspects of the law firm’s business. It includes HR (hiring, training and promoting the most client-centric lawyers) as well as finance (investing only in initiatives that will have a demonstrable impact on clients). It must pervade the entire organisation. Every department in the law firm must see its role through the lens of the client.

Step 3. Build a CX Execution Capability

Besides strong leadership, a successful CX initiative also requires an ‘execution’ capability to ensure that the voice of the client is both captured correctly and acted upon. Execution is more than setting up a client listening post. It involves turning the outputs from those client conversations and collaborative explorations into tangible actions that solve real client problems.

In today’s world, the client personnel involved in buying and consuming legal services extend far beyond the legal department. The client’s voice needs to extend beyond just the GC and her or his legal team. Law firms must think about the ‘influencers’ who are telling those decision makers that “We have to work with Firm X” or “Firm Y really aren’t delivering value for money – we should be looking elsewhere”.

One of the better examples of a good execution capability is Baker McKenzie’s Reinvent programme (Case Study 3). Reinvent started by using client listening to map existing client interactions with the law firm – ‘journey mapping’ as it’s often referred to – but then moved to the next logical level. Baker McKenzie started working with clients to re-engineer processes and even co-creating new services and solutions. The Reinvent programme was developed to establish the governance, skills and infrastructure required to support better client outcomes. This programme focuses both on re-engineering specific processes and services with clients, as well as a way to develop teams across the firm – empowering execution at a grassroots level. Such an approach is a highly effective way to build engagement with the CX process and commitment to its success.

Step 4. Embed Client-Centricity into the DNA of the Organisation

Lawyers are consummate professionals. But are they truly client-centric? Most legal professionals entered the legal industry to practise law. They wanted to advise clients and to mitigate risk. They didn’t join to help CFOs and procurement professionals to cut costs. However, that’s what partners in law firms are being asked to do these days.

Embedding behaviour changes and aligning the firm’s culture with the ‘voice of the client’ takes patience, persistence and continuous effort over a long time. Engagement with clients must be ongoing. Building and sustaining the momentum required to be true client-centric needs a constant stream of input from clients. It also requires constant conversations within the firm about what that input means, and how clients can be better served.

In Case Study 4, we look at Travers Smith’s ability to embed the culture of client-centricity into the DNA of the firm. Silos have been broken down. Close collaboration between lawyers and business services has been achieved. International clients are serviced almost seamlessly. The firm’s senior leadership takes a very active lead in this.

The reason why most law firms are lagging behind might be not that they are inattentive to clients (that is usually patently not the case). It is more likely to be that they simply do not have the systems and processes in place that are required to get input of the quality and detail that can drive continuous improvement. A properly designed CX programme delivers that. Over time, measurable results emerge both in terms of client loyalty (NPS and CRQ scores) and also, more importantly, economic performance.

Conclusion

Earlier, we said that many companies start with Execution. We strongly believe that the first step in a successful CX programme is gaining the right Leadership commitment to putting the client at the heart of everything a law firm does.

Once that leadership is in place, it becomes easier to get the law firm’s strategy aligned to what clients actually need and the CX execution tasks become much easier. With leadership, strategy and execution in place, culture change automatically follows.

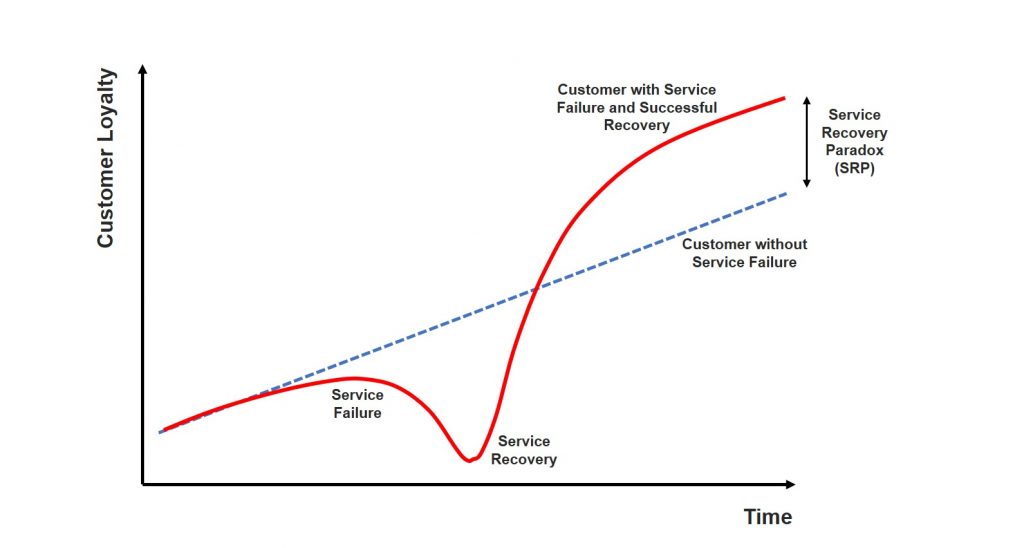

As David Morley’s earlier anecdote reveals, the primary impactors of CX emerge when things go wrong. Clients report four major areas where the law firms that advise them are inconsistent, namely: keeping them informed; dealing with unexpected changes; handling problems; and meeting scope. Feel free to work on these immediately, of course.

But if you want to achieve a step change, that starts at the top.